Aviation Instructor’s Handbook FAA-H-8083-9A: Chapters 7-9

Chapter 7: Instructor Responsibilities and Professionalism

Aviation Instructor Responsibilities

The learning process can be made easier by helping students learn, providing adequate instruction to meet established standards, measuring student performance against those standards, and emphasizing the positive.

Helping Students Learn

The use of standards, and measurement against standards, is key to helping students learn.

Providing Adequate Instruction

The flight instructor analyzes the student’s personality, thinking, and ability.

Students who are permitted to complete every flight lesson without corrections and guidance will not retain what they have practiced as well as those students who have their attention constantly directed to an analysis of their performance.

Standards of Performance

An aviation instructor is responsible for training an applicant to acceptable standards in all subject matter areas, procedures, and maneuvers included in the tasks within each area of operation in the appropriate Practical Test Standard (PTS).

Emphasizing the Positive

Chapter 1, Human Behavior, emphasized that a negative self-concept inhibits the perceptual process, that fear adversely affects student perceptions, that the feeling of being threatened limits the ability to perceive, and that negative motivation is not as effective as positive motivation.

Every effort should be made to ensure instruction is given under positive conditions that reinforce training conducted to standard and modification of the method of instruction when students have difficulty grasping a task.

Minimizing Student Frustrations

Motivate students—more can be gained from wanting to learn than from being forced to learn.

Keep students informed—students feel insecure when they do not know what is expected of them or what is going to happen to them.

Approach students as individuals—when instructors limit their thinking to the whole group without considering the individuals who make up that group, their efforts are directed at an average personality that really fits no one.

Give credit when due—when students do something extremely well, they normally expect their abilities and efforts to be noticed.

Criticize constructively—although it is important to give praise and credit when deserved, it is equally important to identify mistakes and failures.

Be consistent—If the same thing is acceptable one day and unacceptable the next, the student becomes confused.

Admit errors—the instructor can win the respect of students by honestly acknowledging mistakes.

Flight Instructor Responsibilities

The flight instructor’s job is to mold the student pilot into a safe pilot who takes a professional approach to flying.

Instructors should not introduce the minimum acceptable standards for passing the check ride when introducing lesson tasks. The minimum standards to pass the check ride should be introduced during the “3 hours of preparation” for the check ride. [Exam question.]

Physiological Obstacles for Flight Students

Negative sensations can usually be overcome by understanding the nature of their causes. [e.g. What seems like light chop to the instructor may seem to the student like the airplane is coming apart.]

Ensuring Student Skill Set

Flight instructors must ensure student pilots develop the required skills and knowledge prior to solo flight.

The student pilot must show consistency in the required solo tasks: takeoffs and landings, ability to prioritize in maintaining control of the aircraft, proper navigation skills, proficiency in flight, proper radio procedures and communication skills, and traffic pattern operation.

Special emphasis items include, but are not limited to:

1. Positive aircraft control

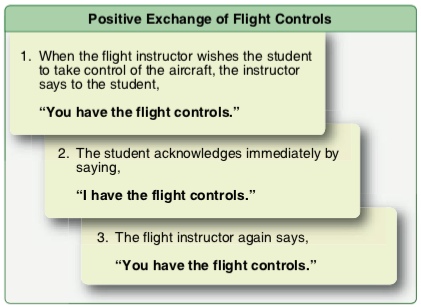

2. Procedures for positive exchange of flight controls

3. Stall and spin awareness (if appropriate)

4. Collision avoidance

5. Wake turbulence and low-level wind turbulence and wind shear avoidance

6. Runway incursion avoidance

7. Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT)

8. Aeronautical decision-making (ADM)/risk management

9. Checklist usage

10. Spatial disorientation

11. Temporary flight restrictions (TFR)

12. Special use airspace (SUA)

13. Aviation security

14. Wire strike avoidance

Aviator’s Model Code of Conduct

1. General Responsibilities of Aviators

2. Passengers and People on the Surface

3. Training and Proficiency

4. Security

5. Environmental Issues

6. Use of Technology

7. Advancement and Promotion of General Aviation

Safety Practices and Accident Prevention

FAA regulations intended to promote safety by eliminating or mitigating conditions that can cause death, injury, or damage are comprehensive, but even the strictest compliance with regulations may not be sufficient to guarantee safety.

The instructor’s advocacy and description of safety practices mean little to a student if the instructor does not demonstrate them consistently. [Exam question.]

Professionalism

Instructors need to commit themselves to continuous, lifelong learning and professional development through study, service, and membership in professional organizations such as the National Association of Flight Instructors (NAFI). Professionals build a library of resources that keeps them in touch with their field through the most current procedures, publications, and educational opportunities.

Sincerity

Teaching an aviation student is based upon acceptance of the instructor as a competent, qualified teacher and an expert pilot.

Acceptance of the Student

The instructor must accept students as they are, including all their faults and problems.

Personal Appearance and Habits

Personal appearance has an important effect on the professional image of the instructor.

Demeanor

The instructor should avoid erratic movements, distracting speech habits, and capricious changes in mood. The successful instructor avoids contradictory directions, reacting differently to similar or identical errors at different times, demanding unreasonable performance or progress, or criticizing a student unfairly, and presenting an overbearing manner or air of flippancy.

Proper Language

Many people object to such language.

Evaluation of Student Ability

Evaluation refers to judging a student’s ability to perform a maneuver or procedure.

Demonstrated Ability

Evaluation of demonstrated ability during flight or maintenance instruction is based upon established standards of performance, suitably modified to apply to the student’s experience and stage of development as a pilot or mechanic.

Keeping the Student Informed

In evaluating student demonstrations of ability, it is important for the aviation instructor to keep the student informed of progress.

Correction of Student Errors

Safety permitting, it is frequently better to let students progress part of the way into the mistake and find a way out.

Students may perform a procedure or maneuver correctly but not fully understand the principles and objectives involved. If the instructor suspects this, students should be required to vary the performance of the maneuver or procedure slightly. [Exam question.]

Aviation Instructors and Exams

Knowledge Test

If the applicant fails a test, the aviation instructor must sign the test after he or she has provided additional training in the areas the applicant failed.

Practical Test

A flight instructor who makes a practical test recommendation for an applicant seeking a certificate or rating should require the applicant to thoroughly demonstrate the knowledge and skill level required for that certificate or rating.

Professional Development

Aviation is changing rapidly, and aviation instructors must continue to develop their knowledge and skills in order to teach successfully in this environment.

Continuing Education

A professional aviation instructor continually updates his or her knowledge and skills.

Government

Educational/Training Institutions

Commercial Organizations

Industry Organizations

Sources of Material

Printed Material

Electronic Sources

The more familiar aviation instructors become with the Internet, the better they are able to adapt to any changes that may occur.

Chapter Summary

This chapter discussed the responsibilities of aviation instructors to the student, the public, and the FAA in the training process. The additional responsibilities of flight instructors who teach new student pilots as well as rated pilots seeking add-on certification, the role of aviation instructors as safety advocates, and ways in which aviation instructors can enhance their professional image and development were explored.

Chapter 8: Techniques of Flight Instruction

According to one definition, safety is the freedom from conditions that can cause death, injury, or illness; damage to/ loss of equipment or property, or damage to the environment. FAA regulations are intended to promote safety by eliminating or mitigating conditions that can cause death, injury, or damage. These regulations are comprehensive, but there has been increasing recognition that even the strictest compliance with regulations may not be sufficient to guarantee safety.

This chapter introduces system safety—aeronautical decision-making (ADM), risk management, situational awareness, and single-pilot resource management (SRM)—in the modern flight training environment.

Flight Instructor Qualifications

A CFI must be thoroughly familiar with the functions, characteristics, and proper use of all flight instruments, avionics, and other aircraft systems being used for training.

Practical Flight Instructor Strategies

The flight instructor should demonstrate good aviation sense at all times:

• Before the flight—discuss safety and the importance of a proper preflight and use of the checklist.

• During flight—prioritize the tasks of aviating, navigating, and communicating. Instill importance of “see and avoid” in the student.

• During landing—conduct stabilized approaches, maintain desired airspeed on final, demonstrate good judgment for go-arounds, wake turbulence, traffic, and terrain avoidance. Use ADM to correct faulty approaches and landing errors. Make power-off, stall-warning blaring, on centerline touchdowns in the first third of runway.

• Always—remember safety is paramount.

Obstacles to Learning During Flight Instruction

• Feeling of unfair treatment

• Impatience to proceed to more interesting operations

• Worry or lack of interest

• Physical discomfort, illness, fatigue, and dehydration

• Apathy due to inadequate instruction

• Anxiety

Unfair Treatment

Students who believe their instruction is inadequate, or that their efforts are not conscientiously considered and evaluated, do not learn well.

Impatience

Impatience is a greater deterrent to learning pilot skills than is generally recognized.

The instructor can correct student impatience by presenting the necessary preliminary training one step at a time, with clearly stated goals for each step. The procedures and elements mastered in each step should be clearly identified in explaining or demonstrating the performance of the subsequent step. [Exam question.]

Worry or Lack of Interest

Students who are worried or emotionally upset are not ready to learn and derive little benefit from instruction. The instructor must be alert and ensure the students understand the objectives of each step of their training, and that they know at the completion of each lesson exactly how well they have progressed and what deficiencies are apparent. Discouragement and emotional upsets are rare when students feel that nothing is being withheld from them or is being neglected in their training.

Physical Discomfort, Illness, Fatigue, and Dehydration

Students who are not completely at ease, and whose attention is diverted by discomforts such as the extremes of temperature, poor ventilation, inadequate lighting, or noise and confusion, cannot learn at a normal rate.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most treacherous hazards to flight safety as it may not be apparent to a pilot until serious errors are made. Fatigue can be either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term). Acute fatigue, a normal occurrence of everyday living, is the tiredness felt after long periods of physical and mental strain, including strenuous muscular effort, immobility, heavy mental workload, strong emotional pressure, monotony, and lack of sleep. [Exam question.]

Acute fatigue is characterized by:

• Inattention

• Distractibility

• Errors in timing

• Neglect of secondary tasks

• Loss of accuracy and control

• Lack of awareness of error accumulation

• Irritability

Chronic fatigue which occurs when there is not enough time for a full recovery from repeated episodes of acute fatigue. Chronic fatigue is a combination of both physiological problems and psychological issues. [Exam question.] [Chronic fatigue can also be caused by sleep apnea.]

Dehydration and Heatstroke

Dehydration is the term given to a critical loss of water from the body. Dehydration reduces a pilot’s level of alertness, producing a subsequent slowing of decision-making processes or even the inability to control the aircraft. The first noticeable effect of dehydration is fatigue. [Exam question.]

Heatstroke is a condition caused by any inability of the body to control its temperature. Onset of this condition may be recognized by the symptoms of dehydration, but also has been known to be recognized only by complete collapse.

Apathy Due to Inadequate Instruction

To hold the student’s interest and to maintain the motivation necessary for efficient learning, well-planned, appropriate, and accurate instruction must be provided.

To be effective, the instructor must teach for the level of the student. The presentation must be adjusted to be meaningful to the person for whom it is intended.

Anxiety

The student must be comfortable, confident in the instructor and the aircraft, and at ease if effective learning is to occur.

Demonstration-Performance Training Delivery Method

This training method has been in use for a long time and is very effective in teaching kinesthetic skills.

Explanation Phase

The explanation phase is accomplished prior to the flight lesson with a discussion of lesson objectives and completion standards, as well as a thorough preflight briefing. In addition to the necessary steps, the instructor should describe the end result of these efforts.

Demonstration Phase

As little extraneous activity as possible should be included in the demonstration if students are to clearly understand that the instructor is accurately performing the actions previously explained.

Student Performance and Instructor Supervision Phases

It is important that students be given an opportunity to perform the skill as soon as possible after a demonstration. Then, the instructor reviews what has been covered during the instructional flight and determines to what extent the student has met the objectives outlined during the preflight discussion.

Evaluation Phase

PBL structures the lessons to confront students with problems that are encountered in real life and forces them to reach real-world solutions. Scenario-based training (SBT), a type of PBL, uses a highly structured script of real world experiences to address aviation training objectives in an operational environment. Collaborative assessment is used to evaluate whether certain learning criteria were met during the SBT.

The Telling-and-Doing Technique

First, the flight instructor gives a carefully planned demonstration of the procedure or maneuver with accompanying verbal explanation. It is important for the demonstration to conform to the explanation as closely as possible. In addition, it should be demonstrated in the same sequence in which it was explained so as to avoid confusion and provide reinforcement.

Student Tells—Instructor Does

In this step, the student actually plays the role of instructor, telling the instructor what to do and how to do it.

Student Tells—Student Does

This is where learning takes place and where performance habits are formed. If the student has been adequately prepared and the procedure or maneuver fully explained and demonstrated, meaningful learning occurs.

Positive Exchange of Flight Controls

Positive exchange of flight controls is an integral part of flight training. It is especially critical during the demonstration-performance method of flight instruction.

Background

Numerous accidents have occurred due to a lack of communication or misunderstanding regarding who had actual control of the aircraft, particularly between students and flight instructors.

Sterile Cockpit Rule

Commonly known as the “sterile cockpit rule,” Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) section 121.542 requires flight crewmembers to refrain from nonessential activities during critical phases of flight. As defined in the regulation, critical phases of flight are all ground operations involving taxi, takeoff, and landing, and all other flight operations below 10,000 feet except cruise flight.

Use of Distractions

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) statistics reveal that most stall/spin accidents occurred when the pilot’s attention was diverted from the primary task of flying the aircraft. Sixty percent of stall/spin accidents occurred during takeoff and landing, and twenty percent were preceded by engine failure. Preoccupation inside or outside the flight deck while changing aircraft configuration or trim, maneuvering to avoid other traffic, or clearing hazardous obstacles during takeoff and climb could create a potential stall/spin situation. The intentional practice of stalls and spins seldom resulted in an accident. The real danger was inadvertent stalls induced by distractions during routine flight situations.

Integrated Flight Instruction

Students are taught to perform flight maneuvers both by outside visual references and by reference to flight instruments. No distinction in the pilot’s operation of the flight controls is permitted, regardless of whether outside references or instrument indications are used for the performance of the maneuver. When this training technique is used, instruction in the control of an aircraft by outside visual references is integrated with instruction in the use of flight instrument indications for the same operations. [Exam question.]

Development of Habit Patterns

It important for the student to establish the habit of observing and relying on flight instruments from the beginning of flight training. It is equally important for the student to learn the feel of the airplane while conducting maneuvers, such as being able to feel when the airplane is out of trim or in a nose-high or nose-low attitude. Students who have been required to perform all normal flight maneuvers by reference to instruments, as well as by outside references, develop from the start the habit of continuously monitoring their own and the aircraft’s performance. The early establishment of proper habits of instrument cross-check, instrument interpretation, and aircraft control is highly useful to the student.

Operating Efficiency

The use of correct power settings and climb speeds and the accurate control of headings during climbs result in a measurable increase in climb performance. Holding precise headings and altitudes in cruising flight definitely increases average cruising performance.

The use of integrated flight instruction provides the student with the ability to control an aircraft in flight for limited periods if outside references are lost. In an emergency, this ability could save the pilot’s life and those of the passengers.

Procedures

Integrated flight instruction begins with the first briefing on the function of the flight controls. This briefing includes the instrument indications to be expected, as well as the outside references to be used to control the attitude of the aircraft.

See and Avoid

From the start of flight training, the instructor must ensure students develop the habit of looking for other air traffic at all times.

• Flight instructors were onboard the aircraft in 37 percent of the accidents in the study.

• Most midair collisions occur in VFR weather conditions during weekend daylight hours.

• The vast majority of accidents occurred at or near nontowered airports and at altitudes below 1,000 feet.

Assessment of Piloting Ability

A well designed assessment provides a student with something constructive upon which he or she can work or build. An assessment should provide direction and guidance to raise the level of performance. There are many types of assessment, but the flight instructor generally uses the review, collaborative assessment (LCG), written tests, and performance-based tests to ascertain knowledge or practical skill levels.

Demonstrated Ability

The assessment must consider the student’s mastery of the elements involved in the maneuver, rather than merely the overall performance.

Postflight Evaluation

Traditionally, flight instructors explained errors in performance, pointed out elements in which the deficiencies were believed to have originated and, if possible, suggested appropriate corrective measures.

With the advent of SBT, collaborative assessment is used whenever the student has completed a scenario. The self-assessment is followed by an in-depth discussion between the instructor and the student which compares the instructor’s assessment to the student’s self-assessment.

First Solo Flight

During the student’s first solo flight, the instructor must be present to assist in answering questions or resolving any issues that arise during the flight. A radio enables the instructor to terminate the solo operation if he or she observes a situation developing.

Post-Solo Debriefing

It is very important for the flight instructor to debrief a student immediately after a solo flight. With the flight vividly etched in the student’s memory, questions about the flight will come quickly.

Correction of Student Errors

Students may perform a procedure or maneuver correctly and not fully understand the principles and objectives involved. When the instructor suspects this, students should be required to vary the performance of the maneuver slightly, combine it with other operations, or apply the same elements to the performance of other maneuvers.

Pilot Supervision

Flight instructors have the responsibility to provide guidance and restraint with respect to the solo operations of their students. Before endorsing a student for solo flight, the instructor should require the student to demonstrate consistent ability to perform all of the fundamental maneuvers. [Exam question.]

Dealing with Normal Challenges

Instructors should teach students how to solve ordinary problems encountered during flight.

Visualization

For example, have a student visualize how the flight may occur under normal circumstances, with the student describing how he or she would fly the flight. Then, the instructor adds unforeseen circumstances. The job of the instructor is to challenge the student with realistic flying situations without overburdening him or her with unrealistic scenarios.

Practice Landings

The FAA recommends that in all student flights involving landings in an aircraft, the flight instructor should teach a full stop landing. Full stop landings help the student develop aircraft control and checklist usage. Aircraft speed and control take precedence over all other actions during landings and takeoffs.

Practical Test Recommendations

The CFI should require the applicant to demonstrate thoroughly the knowledge and skill level required for that certificate or rating. This demonstration should in no instance be less than the complete procedure prescribed in the applicable PTS.

Completion of prerequisites for a practical test is another instructor task that must be documented properly.

Flight instructor recommendations are evidence of qualification for certification, and proof that a review has been given of the subject areas found to be deficient on the appropriate knowledge test.

Aeronautical Decision-Making

The goal of system safety is for pilots to utilize all four concepts (ADM, risk management, situational awareness, and SRM) so that risk can be reduced to the lowest possible level.

ADM is a systematic approach to the mental process used by aircraft pilots to consistently determine the best course of action in response to a given set of circumstances. Risk management is a decision-making process designed to systematically identify hazards, assess the degree of risk, and determine the best course of action associated with each flight. Situational awareness is the accurate perception and understanding of all the factors and conditions within the four fundamental risk elements that affect safety before, during, and after the flight. SRM is the art and science of managing all resources (both onboard the aircraft and from outside sources) available to a single pilot (prior and during flight) to ensure the successful outcome of the flight.

It is estimated that approximately 80 percent of all aviation accidents are human factors related.

Pilot error means that an action or decision made by the pilot was the cause of, or contributing factor to, the accident. This definition also includes the pilot’s failure to make a decision or take action. From a broader perspective, the phrase “human factors related” more aptly describes these accidents since it is usually not a single decision that leads to an accident, but a chain of events triggered by a number of factors. Breaking one link in the chain is all that is usually necessary to change the outcome of the sequence of events.

Traditional pilot instruction has emphasized flying skills, knowledge of the aircraft, and familiarity with regulations. ADM training focuses on the decision-making process and the factors that affect a pilot’s ability to make effective choices.

Timely decision-making is an important tool for any pilot. The pilot who hesitates when prompt action is required, or who makes the decision to not decide, has made a wrong decision.

Declaring an emergency when one occurs is an appropriate reaction. 14 CFR §91.3, “In an inflight emergency requiring immediate action, the pilot in command may deviate from any rule of this part to the extent required to meet that emergency.”

The Decision-Making Process

An understanding of the decision-making process provides students with a foundation for developing ADM skills. Traditionally, pilots have been well trained to react to emergencies, but are not as well prepared to make decisions, which require a more reflective response.

Defining the Problem

This begins with recognizing that a change has occurred or that an expected change did not occur.

One critical error that can be made during the decision-making process is incorrectly defining the problem.

Choosing a Course of Action

After the problem has been identified, the pilot evaluates the need to react to it and determines the actions that may be taken to resolve the situation in the time available.

Implementing the Decision and Evaluating the Outcome

It is important to think ahead and determine how the decision could affect other phases of the flight.

Factors Affecting Decision-Making

Recognizing Hazardous Attitudes

Two steps to improve flight safety are identifying personal attitudes hazardous to safe flight and learning behavior modification techniques.

Attitude: “Description” -> Antidote

Macho: “I can do it.” -> Taking chances is foolish.

Anti-authority” “Don’t tell me.” -> Follow the rules. They are usually right.

Impulsivity: “Do it quickly.” -> It could happen to me.

Invulnerability: “It won’t happen to me.” -> Not so fast. Think first.

Resignation: “What’s the use?” -> I’m not helpless. I can make a difference.

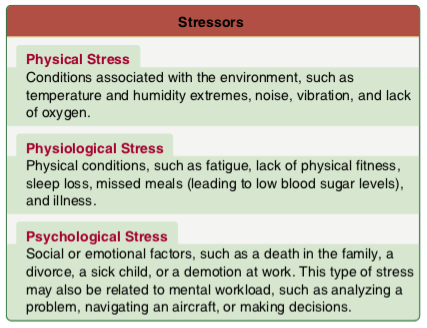

Stress Management

The effects of stress are cumulative and, if not coped with adequately, they eventually add up to an intolerable burden. Performance generally increases with the onset of stress, peaks, and then begins to fall off rapidly as stress levels exceed a person’s ability to cope.[Exam question.]

Use of Resources

During training, CFIs can routinely point out resources to students.

Internal Resources

A thorough understanding of all the equipment and systems in the aircraft is necessary to fully utilize all resources.

Checklists are essential flight deck resources for verifying that the aircraft instruments and systems are checked, set, and operating properly, as well as ensuring that the proper procedures are performed if there is a system malfunction or inflight emergency.

External Resources

ATC can help decrease pilot workload by providing traffic advisories, radar vectors, and assistance in emergency situations. AFSS can provide updates on weather, answer questions about airport conditions, and may offer direction-finding assistance.

Workload Management

Effective workload management ensures that essential operations are accomplished by planning, prioritizing, and sequencing tasks to avoid work overload. As experience is gained, a pilot learns to recognize future workload requirements and can prepare for high workload periods during times of low workload.

Another important part of managing workload is recognizing a work overload situation. The first effect of high workload is that the pilot begins to work faster. As workload increases, attention cannot be devoted to several tasks at one time, and the pilot may begin to focus on one item. When the pilot becomes task saturated, there is no awareness of inputs from various sources; decisions may be made on incomplete information, and the possibility of error increases.

Chapter Summary

This chapter discussed the demonstration-performance and telling-and-doing training delivery methods of flight instruction, SBT techniques, practical strategies flight instructors can use to enhance their instruction, integrated flight instruction, positive exchange of flight controls, use of distractions, obstacles to learning encountered during flight training, and how to evaluate students. After an intensive look at ADM with suggestions for how to interweave ADM, risk management, and SRM into the teaching process, it closes with a discussion of CFI recommendations. Additional information on recommendations and endorsements can be found in Appendix E, Flight Instructor Endorsements.

Chapter 9: Risk Management

Safety risk management in the aviation community is preemptive rather than reactive.

Defining Risk Management

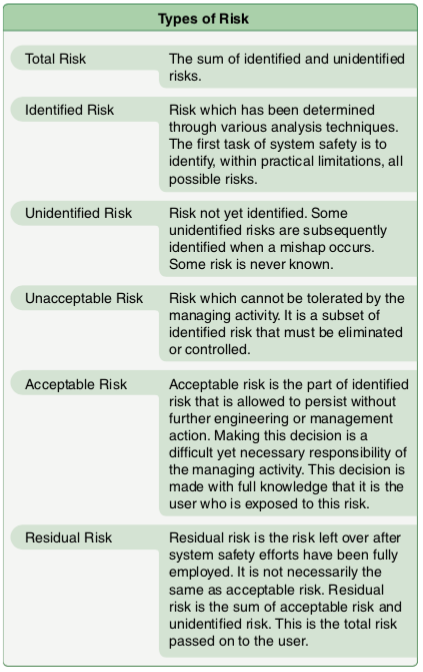

Risk is defined as the probability and possible severity of accident or loss from exposure to various hazards, including injury to people and loss of resources.

• Hazard—a present condition, event, object, or circumstance that could lead to or contribute to an unplanned or undesired event, such as an accident.

• Risk—the future impact of a hazard that is not controlled or eliminated. It is the possibility of loss or injury. The level of risk is measured by the number of people or resources affected (exposure); the extent of possible loss (severity); and likelihood of loss (probability).

• Safety—freedom from those conditions that can cause death, injury, occupational illness, or damage to or loss of equipment or property, or damage to the environment. Therefore, safety is a relative term that implies a level of risk that is both perceived and accepted.

Principles of Risk Management

Accept No Unnecessary Risk

Unnecessary risk is that which carries no commensurate return in terms of benefits or opportunities.

Make Risk Decisions at the Appropriate Level

The appropriate decision-maker is the person who can develop and implement risk controls. The decision-maker must be authorized to accept levels of risk typical of the planned operation.

Accept Risk When Benefits Outweigh the Costs

All identified benefits should be compared against all identified costs.

Integrate Risk Management Into Planning at All Levels

Risks are more easily assessed and managed in the planning stages of an operation. But safety requires the use of appropriate and effective risk management not just in the preflight planning stage, but in all stages of the flight.

Risk Management Process

Risk management is a simple process which identifies operational hazards and takes reasonable measures to reduce risk to personnel, equipment, and the mission.

Step 1: Identify the Hazard

A hazard is defined as any real or potential condition that can cause degradation, injury, illness, death, or damage to or loss of equipment or property. Experience, common sense, and specific analytical tools help identify risks.

Step 2: Assess the Risk

The assessment step is the application of quantitative and qualitative measures to determine the level of risk associated with specific hazards. This process defines the probability and severity of an accident that could result from the hazards based upon the exposure of humans or assets to the hazards.

Step 3: Analyze Risk Control Measures

Investigate specific strategies and tools that reduce, mitigate, or eliminate the risk. All risks have two components:

1. Probability of occurrence

2. Severity of the hazard

Effective control measures reduce or eliminate at least one of these. The analysis must take into account the overall costs and benefits of remedial actions, providing alternative choices if possible.

Step 4: Make Control Decisions

Identify the appropriate decision-maker.

Step 5: Implement Risk Controls

A plan for applying the selected controls must be formulated, the time, materials, and personnel needed to put these measures in place must be provided.

Step 6: Supervise and Review

Once controls are in place, the process must be reevaluated periodically to ensure their effectiveness. The risk management process continues throughout the life cycle of the system, mission, or activity.

Implementing the Risk Management Process

• Apply the steps in sequence—each step is a building block for the next

• Allocate the time and resources to perform all steps in the process.

• Apply the process in a cycle—the “supervise and review” step should include a brand new look at the operation being analyzed to see whether new hazards can be identified.

• Involve people in the process—the people who are actually exposed to risks usually know best what works and what does not.

Level of Risk

The level of risk posed by a given hazard is measured in terms of:

• Severity (extent of possible loss)

• Probability (likelihood that a hazard will cause a loss)

Assessing Risk

Every flight has hazards and some level of risk associated with it. It is critical that pilots and especially students are able to differentiate in advance between a low-risk flight and a high-risk flight, and then establish a review process and develop risk mitigation strategies to address flights throughout that range.

Likelihood of an Event

• Probable—an event will occur several times.

• Occasional—an event will probably occur sometime.

• Remote—an event is unlikely to occur, but is possible.

• Improbable—an event is highly unlikely to occur.

Severity of an Event

• Catastrophic—results in fatalities, total loss

• Critical—severe injury, major damage

• Marginal—minor injury, minor damage

• Negligible—less than minor injury, less than minor system damage

Mitigating Risk

After determining the level of risk, the pilot needs to mitigate the risk

IMSAFE Checklist

1. Illness—Am I sick? Illness is an obvious pilot risk.

2. Medication—Am I taking any medicines that might affect my judgment or make me drowsy?

3. Stress—Stress causes concentration and performance problems. While the regulations list medical conditions that require grounding, stress is not among them.

4. Alcohol—Have I been drinking within 8 hours? Within 24 hours?

5. Fatigue—Am I tired and not adequately rested? Fatigue continues to be one of the most insidious hazards to flight safety, as it may not be apparent to a pilot until serious errors are made.

6. Emotions-A pilot who experiences an emotionally upsetting event should refrain from flying until the pilot has satisfactorily recovered.

The PAVE Checklist

Pilot in command (PIC), Aircraft, enVironment, and External pressures

Three-P Model for Pilots

Risk management is a decision-making process designed to perceive hazards systematically, assess the degree of risk associated with a hazard, and determine the best course of action.

• Perceives the given set of circumstances for a flight.

• Processes by evaluating the impact of those circumstances on flight safety.

• Performs by implementing the best course of action.

In the first step, the goal is to develop situational awareness by perceiving hazards, which are present events, objects, or circumstances that could contribute to an undesired future event. In this step, the pilot systematically identifies and lists hazards associated with all aspects of the flight: pilot, aircraft, environment, and external pressures.

In the second step, the goal is to process this information to determine whether the identified hazards constitute risk, which is defined as the future impact of a hazard that is not controlled or eliminated. The degree of risk posed by a given hazard can be measured in terms of exposure (number of people or resources affected), severity (extent of possible loss), and probability (the likelihood that a hazard will cause a loss).

In the third step, the goal is to perform by taking action to eliminate hazards or mitigate risk, and then continuously evaluate the outcome of this action.

The decision-making process is a continuous loop of perceiving, processing, and performing.

Pilot Self-Assessment

Just as a checklist is used when preflighting an aircraft, a personal checklist based on such factors as experience, currency, and comfort level can help determine if a pilot is prepared for a particular flight.

Situational Awareness

Situational awareness is the accurate perception and understanding of all the factors and conditions within the four fundamental risk elements that affect safety before, during, and after the flight.

Obstacles to Maintaining Situational Awareness

Fatigue, stress, or work overload can cause the pilot to fixate on a single perceived important item rather than maintaining an overall awareness of the flight situation. A contributing factor in many accidents is a distraction, which diverts the pilot’s attention from monitoring the instruments or scanning outside the aircraft.

As fatigue progresses, it is responsible for increased errors of omission, followed by errors of commission, and microsleeps, or involuntary sleep lapses lasting from a few seconds to a few minutes.

Warning Signs of Fatigue

Eyes going in and out of focus

Head bobs involuntarily

Persistent yawning

Spotty short-term memory

Wandering or poorly organized thoughts

Missed or erroneous performance of routine procedures

Degradation of control accuracy

Complacency presents another obstacle to maintaining situational awareness. Defined as overconfidence from repeated experience on a specific activity, complacency has been implicated as a contributing factor in numerous aviation accidents and incidents.

Operational Pitfalls

There are numerous classic behavioral traps that can ensnare the unwary pilot. The basic drive to demonstrate achievements can have an adverse effect on safety, and can impose an unrealistic assessment of piloting skills under stressful conditions.

Single-Pilot Resource Management (SRM)

Single pilot resource management (SRM) is defined as the art and science of managing all the resources (both onboard the aircraft and from outside sources) available to a single pilot (prior to and during flight) to ensure the successful outcome of the flight. SRM includes the concepts of ADM, Risk Management (RM), Task Management (TM), Automation Management (AM), Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) Awareness, and Situational Awareness (SA).

SRM and the 5P Check

SRM is about gathering information, analyzing it, and making decisions. Learning how to identify problems, analyze the information, and make informed and timely decisions is not as straightforward as the training involved in learning specific maneuvers. Learning how to judge a situation and “how to think” in the endless variety of situations encountered while flying out in the “real world” is more difficult. There is no one right answer in ADM; rather, each pilot is expected to analyze each situation in light of experience level, personal minimums, and current physical and mental readiness level, and make his or her own decision.

The 5 Ps consist of “the Plan, the Plane, the Pilot, the Passengers, and the Programming.” The 5P concept relies on the pilot to adopt a scheduled review of the critical variables at points in the flight where decisions are most likely to be effective. The second easiest point in the flight to make a critical safety decision is just prior to takeoff. The third place to review the 5 Ps is at the midpoint of the flight. The last two decision points are just prior to decent into the terminal area and just prior to the final approach fix, or if VFR just prior to entering the traffic pattern, as preparations for landing commence.

The Plan

The plan can also be called the mission or the task. The plan should be reviewed and updated several times during the course of the flight.

The Plane

Both the plan and the plane are fairly familiar to most pilots. The plane consists of the usual array of mechanical and cosmetic issues that every aircraft pilot, owner, or operator can identify. With the advent of advanced avionics, the plane has expanded to include database currency, automation status, and emergency backup systems that were unknown a few years ago.

The Pilot

The traditional “IMSAFE” checklist is a good start.

The Passengers

One of the key differences between CRM and SRM is the way passengers interact with the pilot. Pilots also need to understand that non-pilots may not understand the level of risk involved in the flight.

The Programming

While programming and operation of these devices are fairly simple and straightforward, unlike the analog instruments they replace, they tend to capture the pilot’s attention and hold it for long periods of time.

The SRM process is simple. At least five times before and during the flight, the pilot should review and consider the “Plan, the Plane, the Pilot, the Passengers, and the Programming” and make the appropriate decision required by the current situation.

Information Management

The volume of information presented in aviation training is enormous, but part of the process of good SRM is a continuous flow of information in and actions out.

Task Management

Task management (TM), a significant factor in flight safety, is the process by which pilots manage the many, concurrent tasks that must be performed to safely and efficiently fly a modern aircraft. A task is a function performed by a human, as opposed to one performed by a machine.

Task management entails initiation of new tasks; monitoring of ongoing tasks to determine their status; prioritization of tasks based on their importance, status, urgency, and other factors; allocation of human and machine resources to high-priority tasks; interruption and subsequent resumption of lower priority tasks; and termination of tasks that are completed or no longer relevant.

Automation Management

Automation management is the demonstrated ability to control and navigate an aircraft by means of the automated systems installed in the aircraft. One of the most important concepts of automation management is knowing when to use it and when not to use it.

Teaching Decision-Making Skills

System safety flight training occurs in three phases. First, there are the traditional stick and rudder maneuvers. In order to apply the critical thinking skills that are to follow, pilots must first have a high degree of confidence in their ability to fly the aircraft. Next, the tenets of system safety are introduced into the training environment as students begin to learn how best to identify hazards, manage risk, and use all available resources to make each flight as safe as possible. This can be accomplished through scenarios that emphasize the skill sets being taught. Finally, the student is introduced to more complex scenarios demanding focus on several safety-of-flight issues. Thus, scenarios should start out rather simply, then progress in complexity and intensity as the student can handle the learning load.

It is also important for the flight instructor to remember that a good scenario:

• Is not a test.

• Will not have a single correct answer.

• Does not offer an obvious answer.

• Engages all three learning domains.

• Is interactive.

• Should not promote errors.

• Should promote situational awareness and opportunities for decision-making.

• Requires time-pressured decisions.

Assessing SRM Skills

In SRM assessment, instructors must learn to assess students on a different level. How did the student arrive at a particular decision? What resources were used? Was risk assessed accurately when a go/no-go decision was made? Did the student maintain situational awareness in the traffic pattern? Was workload managed effectively during a cross-country flight? How does the student handle stress and fatigue?

Instructors should utilize SBT to create lessons that are specifically designed to test whether students are applying SRM skills. Planning a flight lesson in which the student is presented with simulated emergencies, a heavy workload, or other operational problems can be valuable in assessing the student’s judgment and decision-making skills

SRM grades are based on these four components: Explain, Practice, Manage/Decide, Not Observed

The purpose of the self-assessment is to stimulate growth in the student’s thought processes and, in turn, behaviors. The self-assessment is followed by an in-depth discussion between the flight instructor and the student which compares the CFI’ s assessment to the student’ s self-assessment.

Chapter Summary

This chapter introduced aviation instructors to the underlying concepts of safety risk management, which the FAA is integrating into all levels of the aviation community.